Interview with Christopher Gibbs & John Gingerich

March 2, 2018

The Chamber Music Society’s winter festival recreates four concerts that were originally performed in Vienna in the 1820s as part of a series programmed by violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh (1776-1830). Though he’s virtually unknown today, Schuppanzigh had a considerable influence on Viennese concert life in the early 19th century as a performer and concert organizer. He started a trend where chamber music was increasingly performed by professionals in the concert hall rather than amateurs at home. He also had a close working relationship with Beethoven, and he programmed almost all of Beethoven’s chamber music between 1823 and 1830.

Music historians Christopher H. Gibbs and John M. Gingerich brought Schuppanzigh’s fascinating world to the attention of CMS. They have reconstructed Schuppanzigh’s series and provided a wealth of historical information on his concerts and his continuing influence on chamber music performance today.

CMS: When did you first get interested in Schuppanzigh? How did you reconstruct his series?

CG & JG: We became interested in him independently through our work on Franz Schubert. John noticed that the beginning of Schuppanzigh’s 1820s concert series coincided with a whole new phase in Schubert’s career, what he later called “Schubert’s Beethoven Project” and that was the topic of his doctoral thesis at Yale and of his first book for Cambridge University Press. Christopher wondered why Schuppanzigh, after promoting Schubert’s music for some years, did not perform along with other members of his group at the composer’s big concert on 26 March 1828, the first anniversary of Beethoven’s death. We both began to explore the larger context of Schuppanzigh’s series and at some point realized we were working on the same thing and so pulled forces. To reconstruct the more than 100 chamber concerts Schuppanzigh presented between 1823 and 1830 we started looking for programs in the archives of the Friends of Music (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde) and elsewhere in Vienna. We also searched newspaper notices, which got easier as more sources became available online. A big breakthrough came when we found published annual compilations of all the public concerts performances in Vienna over a period of four years. John is now completing a book that examines the full range of Schuppanzigh’s activities.

CMS: Before Schuppanzigh, string quartets were either performed privately for the nobility or sight-read at home by amateurs. How do you think that influenced Schuppanzigh’s quartet and its approach to rehearsals and public performances?

CG & JG: In general string players of the time seem to have been very good sight-readers and performance standards were remarkably low compared with what we expect now. Although for his contemporaries the Schuppanzigh Quartet offered incredibly polished performances, we might not be similarly impressed by today’s standards. Instead of hours of rehearsal they tended to rely on years of playing together to make a performance tight.

CMS: Beethoven’s Septet, Op. 20, was one of his most popular pieces in his lifetime and one of the most frequently performed on Schuppanzigh’s series. Why do you think it was so admired?

CG & JG: The work has everything: memorable tunes, fun, excitement, some tender moments, plus an unusual combination of instruments, a miniature orchestra of sorts, that particularly brings out the special character of the clarinet and horn. All that, and it is easy to follow and listen to.

CMS: Tell me about Schuppanzigh’s personal relationship with Beethoven.

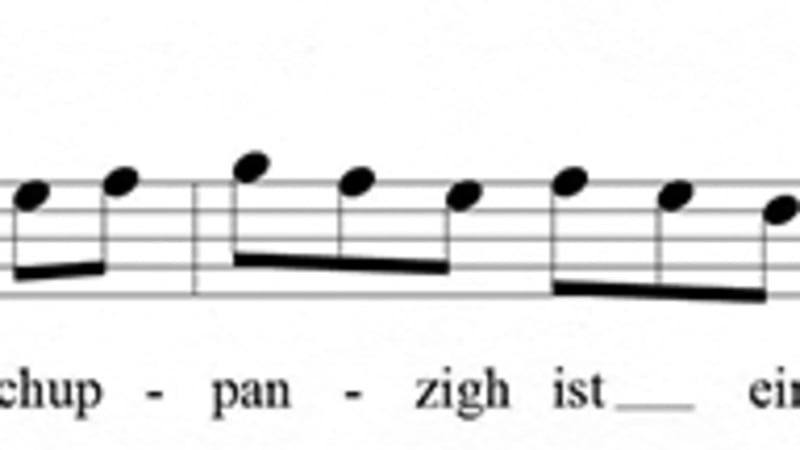

CG & JG: There seems to have been a great deal of trust and loyalty, but they were not intimate friends. In the conversation books, at least, Schuppanzigh always treated Beethoven with deference and respect, if not awe and reverence, and tolerated good-naturedly Beethoven’s sometimes cruel jokes at his expense. Beethoven held Schuppanzigh’s musicianship in high regard, and was, for example, willing to jeopardize the arrangements for the premiere of the Ninth Symphony in order to make sure that Schuppanzigh would lead the orchestra. But when Schuppanzigh made a mess of the premiere of the String Quartet in E-flat major, Op. 127, Beethoven took no responsibility for his late delivery of the parts, reneged on his agreement with Schuppanzigh, and gave the piece to a rival to perform, a rival who played it with the other members of Schuppanzigh’s quartet! That must have been one of the lowest points in Schuppanzigh’s life. Some good-natured affection comes in various musical jokes, canons, that Beethoven wrote for Schuppanzigh.

The Chamber Music Society’s winter festival begins on March 13 with a lecture by Christopher Gibbs and a concert originally performed on Schuppanzigh’s series in 1827. The festival continues on March 18, 23, and 27.

Interview by Laura Keller