The Kreutzer Sonata: Love, Murder, and the Violin

September 27, 2018

History unfolds in mysterious ways. When Beethoven dedicated his ninth violin sonata to Rodolphe Kreutzer in 1805, the violinist was already internationally renowned for his virtuosity and celebrated for a new style of violin playing characterized by a full tone and legato (singing) style. Kreutzer also composed many works for the stage, and he went on to become chief conductor and later music director of the Paris Opéra. Yet his popularity began to wane even before his death and he would be little remembered today if it wasn’t for Beethoven’s sonata. In a twist of fate, his name ended up on not just one but three major works of art (and many minor ones) that spanned more than 100 years and explored love, murder, religion, social issues, and more.

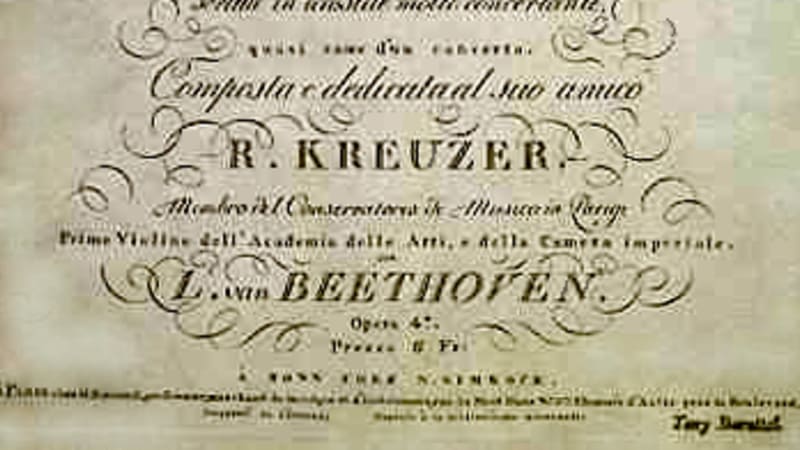

Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata

Beethoven first met Kreutzer in 1798. Not much is known about their relationship but the two men don’t appear to have been close. Beethoven did appreciate Kreutzer’s playing, writing, “I prefer his modesty and natural behavior to all the exterior without any interior, which is characteristic of most virtuosos.” When Beethoven dedicated the Violin Sonata in A major, Op. 47, to Kreutzer, the violinist wasn’t told ahead of time. Kreutzer probably never performed the sonata publicly and the composer Berlioz reported that he called it “outrageously unintelligible.” The dedication of Beethoven’s violin sonata was only a minor event at a time when Kreutzer was composing more and concertizing less.

Beethoven’s last-minute dedication to Kreutzer was made after the sonata was completed and premiered. It was originally written for George Bridgetower, a violin virtuoso who was visiting Vienna in the spring of 1803. Beethoven and Bridgetower got along like a house on fire and, when they booked a concert together (with Beethoven playing the piano), the composer rushed to finish a violin sonata he had begun the previous year. The pair premiered the sonata on May 24, 1803, with very little rehearsal and to great audience acclaim. The honeymoon came to a swift end, however, when Bridgetower made an unflattering comment about a woman that Beethoven respected (exactly what he said is unknown). Beethoven, who generally held grudges forever, was furious. He never spoke to Bridgetower again, and he changed the sonata’s dedication to Kreutzer before its publication in 1805. Bridgetower was bitter for the rest of his life.

Tolstoy's novella

That was more or less the end of the story until 1889, when Leo Tolstoy wrote a story entitled The Kreutzer Sonata. In Tolstoy's novella, a man describes how he and his wife became emotionally estranged and lived in constant tension. Then a handsome violinist comes into their life, and the violinist and the narrator’s piano-playing wife perform a musical evening in the couple’s home. He explains:

I was in torture, especially because I was sure that toward me she had no other feeling than of perpetual irritation, sometimes interrupted by the customary sensuality, and that this man,—thanks to his external elegance and his novelty, and, above all, thanks to his unquestionably remarkable talent, thanks to the attraction exercised under the influence of music, thanks to the impression that music produces upon nervous natures,—this man would not only please, but would inevitably, and without difficulty, subjugate and conquer her, and do with her as he liked.

-The Kreutzer Sonata, Tolstoy

At the climax of the story, the man comes home late at night from a business trip to find his wife eating alone with the violinist. He gets so jealous at this breach of social etiquette that he kills her. He goes on trial and spends 11 months in prison but is ultimately freed.

Seesawing wildly between feminism and misogyny, Tolstoy’s novella hits on many hot-button issues of the late 19th century: it paints a vivid picture of two people trapped in a loveless marriage, it explores how society suffers when women don’t have equal rights, and it promotes abstinence through a lot of hand-wringing about extra-marital sex. The novella ends with a guilt-ridden religious message renouncing desire, “We must understand the real meaning of the words of the Gospel,—Matthew, V. 28,—‘that whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery’; and these words relate to the wife, to the sister, and not only to the wife of another, but especially to one’s own wife.” Tolstoy’s novella had very little to do with Beethoven “Kreutzer” sonata specifically—just as Beethoven’s sonata had very little to do with Kreutzer. Instead Tolstoy condemns the raw emotional power of music in general.

Janáček’s Kreutzer Quartet

Tolstoy’s novella was immediately popular and it inspired many other works of art: plays, paintings, and even two novels from his own wife who naturally objected to the extremely unflattering (and semi-autobiographical) portrayal of the narrator’s wife. Composer Leoš Janáček read and re-read the novella and owned a heavily-annotated copy in the original Russian. He wrote a (now lost) piano trio on Tolstoy’s novella in 1909, and in 1923 edited some of the trio’s material into a string quartet.

The story of The Kreutzer Sonata had special resonance with Janáček by 1923. He was in his own difficult marriage and infatuated with a much younger woman named Kamila Stösslová, who was herself married. He wrote her hundreds of letters in the last 11 years of his life, and he told her that many of his late works were written with her in mind. About his string quartet, Janáček wrote to Stösslová, “I was imagining a poor woman, tormented and run down, just like the one the Russian writer Tolstoy describes in his Kreutzer Sonata.”

The music is as tormented as the novella. Janáček sounds like he’s telling a story, but the music doesn’t seem to chronologically correspond to the events of the story, and the composer didn’t leave a detailed explanation. He brings a whole batch of post-World War I techniques and ideas to draw the listener into a world of anguish and desire:

- Janáček doesn’t make smooth transitions. When he wants to start a new section, he just… does it.

- He liked to musically notate the speech of those around him. His rhythms are loosely inspired by the Czech language.

- To build tension and create unity, Janáček would repeat a melody at different speeds through the course of the piece.

- By the same token, he uses many, many different tempos. The piece changes tempos every few bars.

The third movement has all of the above, plus it’s based on themes from the first movement of Beethoven’s violin sonata, the movement that most affected Tolstoy. A Beethoven quote starts immediately in the first violin and is echoed by the cello. To ratchet up the tension, Janáček changes Beethoven’s major to minor, and, to remind us of Tolstoy, he marks the passage leggiero, paventoso (lightly, fearfully). Soon another motive is heard— its two repeated notes vaguely resemble Beethoven’s first movement main theme. Janáček cleverly evokes both themes from Beethoven’s first movement in reverse order, and he even sort of combines them (1:55 in the video below). The movement (and the entire piece) is by turns timid and aggressive, longing and fearful, uninhibited and shy—an evocative picture of the “poor woman” that Janáček described to Stösslová.

Listen to the whole piece here.

Janáček’s quartet is an amazing synthesis. He takes musical snippets from Beethoven’s violin sonata and uses them as building blocks to create a wordless story of desire and intrigue. His emotional language is reminiscent of Tolstoy’s novella with the added layer that Janáček himself was a musician pursuing a married woman.

What Kreutzer would have thought of all this is anyone’s guess. Over 120 years and across multiple countries, his name became not just that of a remarkable violinist but synonymous with passion, infidelity, and the power of music to make people lose control. Aside from his etudes, Kreutzer’s own compositions have largely been forgotten but his name lives on through the works of others.

Article by Laura Keller, Editorial Manager.