A Trio Tour

September 30, 2019

The word “Trio” appears on concert programs all the time, usually attached to a minuet or scherzo movement in a symphony or a piece of chamber music. We take for granted the fact the corresponding section in the music rarely features three instruments. So where does this (instrumentally misleading) label come from?

The story behind trio sections begins with the history of the minuet, a popular dance form that came into fashion in France in the 17th century. This stately, aristocratic dance in 3/4 time featured individual couples completing step patterns of 12 measures while the rest of the party looked on. In the diagram below from French dancing master Pierre Rameau’s manual Le maître à danser, the court observes as a couple advances (3 & 4) and bows to the King (1 & 2) before starting their dance.

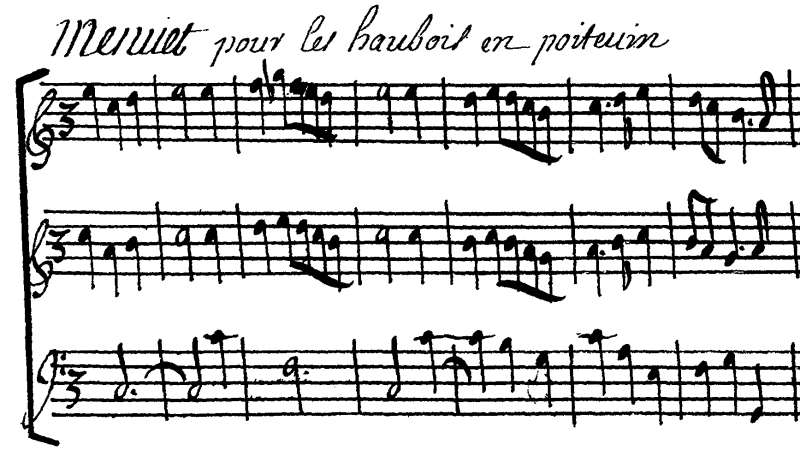

The minuet was a long dance, both in terms of the number of steps it included, and because it could sometimes take well over 100 measures for the ending of the dance pattern to coincide with the end of an appropriate musical section. As a result, the music that accompanied minuets was extremely repetitive. Composers began to write alternate sections to go between duplications of the main minuet music, providing listeners with some variety of melody and timbre while increasing the length of the composition to fit the dance. For example, French composer Jean Baptiste Lully (1632-87) wrote minuets that alternated a full string orchestra with a smaller “Trio” of two oboes and a bassoon, as in the excerpt below from his 1670 score to the comédie-ballet Le Bourgeois gentilhomme.

One of Lully’s admirers who adopted similar practices, German composer George Muffat (1653-1704), described the emotional consequences of such “Trio” contrasts for listeners, saying “through the rigorous observation of this opposition or contrast between…the fullness of the large [string] choir and the tenderness of the trio, the ear will be transported to a state of special amazement, just as the eye is so transported by the contrast of light and shadow.” This alternating instrumentation technique was quite popular and by the end of the 17th century, it was common practice to label a contrasting, alternate section in a dance form as a “Trio” regardless of the actual instrumentation. According to Bach scholar Michael Marissen, these intervening trio sections held an additional, elite social connotation: only the nobles were supposed to dance during this music. The rest of the party would watch and then join in for the return of the Tutti minuet section.

The last movement of J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 (c. 1720) features a series of three such intervening dances sandwiched between many iterations of a minuet refrain. Each of the trio sections puts a different solo instrument group on display and represents a particular national style. The first, “French” trio features two oboes and bassoon, the scoring that Lully was known for. The next interlude is a sometimes-soothing, sometimes-galloping Polish dance, the Polonaise, featuring strings. The upbeat, final trio is what Marissen describes as “Germanic hunt music.” It is in a highly contrasting duple meter and employs the unique, wind-band-like combination of oboes and horns.

Watch Bach's full Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046 here.

In the Classical period, the form became more stylized and concise, usually featuring just one trio in between two repetitions of the same minuet. Trio sections often still included a thinning or simplification in texture, but Classical composers began to focus on ways to create variety other than featuring fewer instruments. For example, they frequently used trio sections to explore contrasting key areas. W.A. Mozart, in his C minor Serenade for Winds (c. 1782), writes a trio in sunny C major that represents a total inversion of the preceding, melancholy C minor minuet.

Watch Mozart's full Serenade for Winds in C minor here.

During this period, it also became common for composers to replace minuet movements with scherzos (literally “jokes”), trading out the stately, aristocratic character of the form’s origins for a more humorous and rustic type of dance. The trios remained, however. Joseph Haydn, in his 1772 “Joke” Quartet, follows a leaping, vigorous scherzo with a cheeky, playful trio.

Watch Haydn's full "Joke" Quartet here.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, scherzo movements became far more popular than minuets in the context of chamber music and symphonies. Romantic scherzos still followed the Classical formula of an outer dance bookending a contrasting inner trio section, but the trios grew even more divergent in character from those outer sections. A clear example of this can be heard in Franz Schubert’s 1828 Cello Quintet. The scherzo section is an exuberant and virtuosic outburst in C major. For the middle section, Schubert moves to the remote key of D-flat major and changes the time-signature and tempo indication to a 4/4 Andante sostenuto. This trio is a warm, simple, and yet tragically-tinged break from the energetic and triumphant music that occupies the rest of the movement—contrasting music that is most worthy of Muffat’s allusion to light and shadow.

Watch Schubert's full Cello Quintet here.

By the time 20th-century modernists like Alban Berg were writing atonal chamber music, older formal types were often eschewed in favor of new systems of musical organization. Yet the designation of “Trio” had become so synonymous with alternate or contrasting sections that it continued to be used in score indications and movement titles. Berg, in the third movement of his 1926 Lyric Suite, includes a passionate Trio estatico (Ecstatic Trio).

Berg Lyric Suite for String Quartet with Soprano, Allegro misterioso-Trio estatico

Performed by the Escher String Quartet.

The outer sections—designated not Minuet or Scherzo but Allegro misterioso—are full of flickering special effects and extended techniques, a far cry from the rhythmically grounded dances heard in Baroque, Classical, and Romantic works. But by the 20th and 21st centuries, our understanding of “Trio” had evolved well beyond the form’s origins as a minuet lengthener featuring wind melodies that only a prince could dance to. Rather, we now see “Trio” as an indication to expect music of intentional and meaningful contrast created by a composer’s inventive use of novel themes, textures, rhythms, harmonies, and characters.

Join us this Fall and Winter at CMS for some terrific trios:

Haydn’s “Joke” Quartet, October 20th

Schubert’s Cello Quintet, October 27th

Berg’s Lyric Suite, November 8th

Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, December 13th, 15th, and 17th

Mozart’s C minor Wind Serenade, January 30th

Article by Nicky Swett, Temporary Editorial Manager.

Learn more:

Little, Meredith Ellis. 2001. "Minuet.” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

Marissen, Michael. 1995. “Concerto Styles and Significations in Bach's First Brandenburg Concerto.” Bach Perspectives, Volume 1, 79–101.

Muffat, George and Wilson, David. 2001. George Muffat on Performance Practice. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Rameau, Pierre. 1728. The dancing-master: or, The art of dancing explained. London: J. Brotherton.

Schwandt, Erich. 2001. "Trio." The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

Special thanks to David Peter Coppen for his research assistance.