Nudging Notation: Communicating New Ideas with Traditional Scores

November 7, 2023

By Nicky Swett

A great challenge for many composers of the 21st century is how to engage with music notation. So much that is written today contains a multitude of cultural influences, which might include improvised or non-notated musical traditions. But when the final performance of a work will be delivered by players on Western classical instruments, odds are that the concert will be based on a score. How can a composer visually communicate potentially unfamiliar gestures, improvisatory elements, or new conceptions of rhythm to performers so that they can internalize those ideas and express them to an audience?

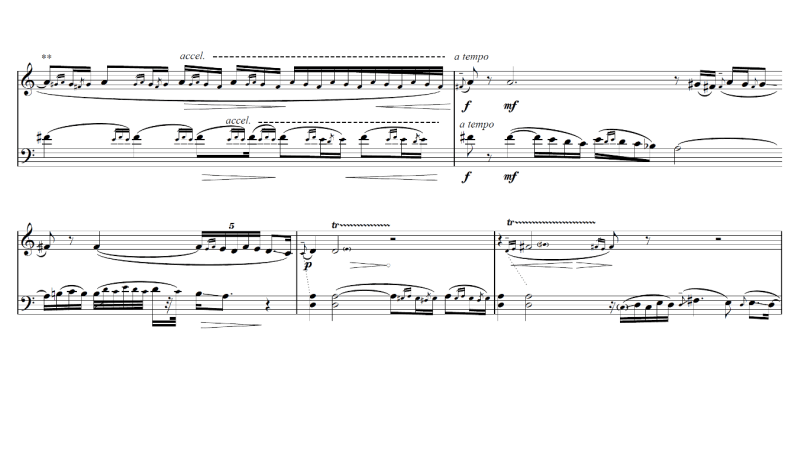

In the scores of Reena Esmail, the difference between small- and large-print notes is particularly important. Many of her compositions draw on Hindustani music from North India, which involves performers improvising large structures from sets of melodic patterns. Vocalists and instrumentalists engage in practices of strategic ornamentation, quickly moving through and around some pitches to emphasize the role of others in a given context. Esmail communicates such hierarchies of emphasis in her scores through a beautiful combination of tiny grace notes, other smaller notes, and full-sized notes. Looking at the music, a player knows immediately which notes to land on and which to use as whirling generators of horizontal motion, elements of performance style that are not easy to show when most of the pitches one sees are the exact same size.

Officially, in Western music notation, when notes are grouped together under a thick line (called a “beam”), the score is telling a player that they are the same length. In reality, no performer plays consecutive notes exactly the same length. There is a subtle give and take within a beat and within a measure. A performer might slow down over the course of a few ostensibly equal notes, or speed up, because it feels natural to the character and rhythmic feeling of the music.

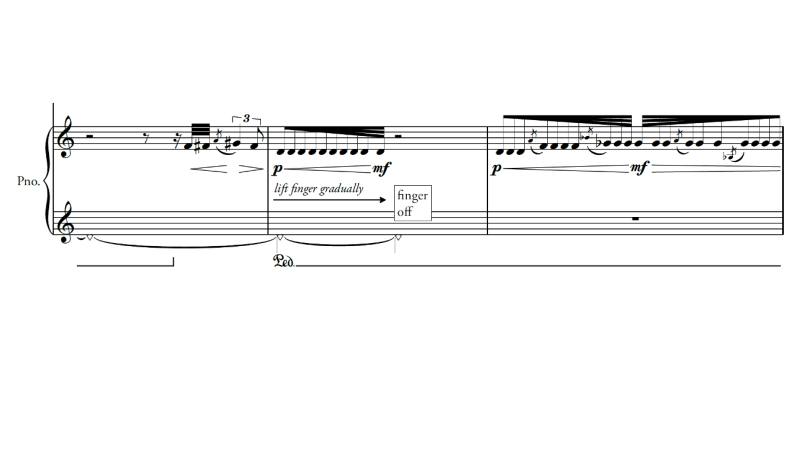

Composers can manipulate the shape of the beams that group together sets of notes in order to explicitly show such internal modifications of speed. In the second measure in this passage from Saad Haddad’s Kaman Fantasy, the pianist plays a sequence of ten notes. The beam that unites them gradually splits into three, which means that by the end of the sequence the music should be three times faster than at the start. A similar acceleration is communicated in the next measure, followed by a mirrored, slowing figure. The visual display gives a clean analogy for the process of speeding up and decelerating, and such modified beams are more flexible and efficient than the written indications of “accelerando” or “rallentando,” both more traditional ways of expressing such changes.

There are many limitations to notation practice, and there is much about music and performance that a score simply can’t capture. Still, composers and researchers are constantly finding clever ways to revise how music is engraved in order to enhance the amount and richness of information that can be delivered with this long-lived system of symbols.

Cellist, writer, and music researcher Nicky Swett is a program annotator and editorial contributor at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center.